Heinrich Pyramid Discussion – Where are you?

I thought it was time to bring this topic up again.

Back in 2007, I wrote a short article and gave several talks at professional society conferences about the “accident pyramid” or the “Heinrich Pyramid.”

At the time, people were saying that the pyramid wasn’t accurate or useful for safety improvement.

I think that much of the misunderstanding and debate starts with a misuse of what the pyramid represents.

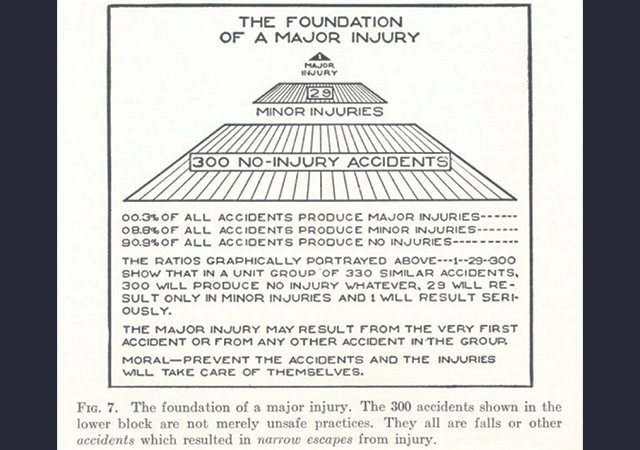

The original pyramid was based on Heinrich’s work in the insurance industry in the 1920’s and 1930’s (see above). The writing below the pyramid says that of 330 similar events, 1 will result in a major injury, 29 will result in a minor injury, and 300 will result in no injury at all.

Thus, because the events are similar, ALL 330 events could have caused a major injury, but 329 did not because of luck or some other circumstance.

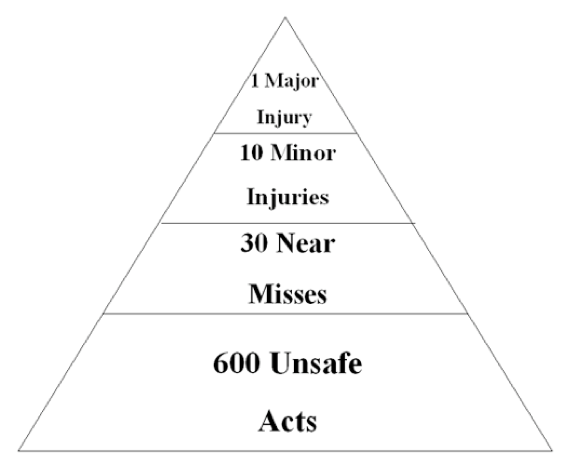

As time went on, people modified Heinrich’s Pyramid. There was the Frank Bird modification (Loss Control Management: Practical Loss Control Leadership, 1969):

People interpreted this graph as meaning that for every major injury there would be 600 unsafe acts. Sometimes people didn’t say that the unsafe acts had to be capable of causing the major injury.

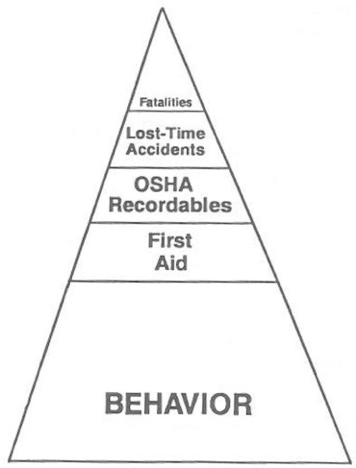

Also, there was the Krause, Hindley, and Hodson Pyramid (The Behavior-Based Safety Process, 1990):

This replaced many of the terms on the pyramid and introduces behavior as the ultimate cause of injuries and fatalities.

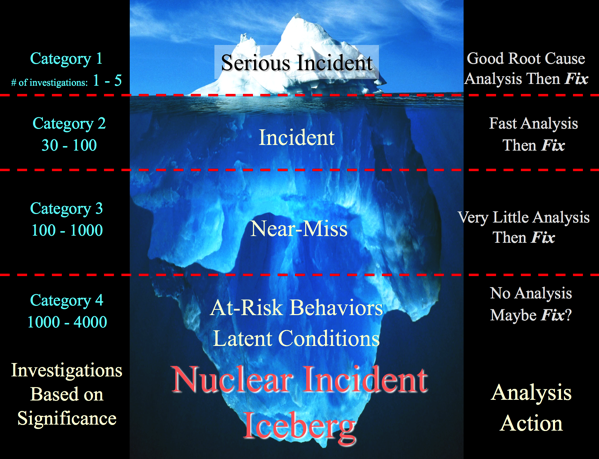

And finally, the nuclear safety iceberg:

Which once again, focussed on behaviors and latent conditions and didn’t mention the significance of the Safeguard that was being weakened.

From these new pyramids, people got the idea that focusing on unsafe acts and behaviors could stop major accidents. However, many lost the idea that the behaviors or unsafe acts had to be capable of causing a major accident/fatality or removing a Safeguard to a major accident or fatality. Thus, people started focusing on any small injury as a way of preventing big injuries or small problems to prevent reactor meltdowns.

However, stopping paper cuts won’t prevent major process safety related accidents or industrial safety fatalities.

None the less, some safety programs were mislead into thinking that stopping first aid cases would lead to an end to fatalities. Many programs were overwhelmed by small problems to investigate and they started using questionable root cause analysis tools to speed up the investigations.

Thus, even incidents which had the potential to cause a major accident/process safety disaster/fatality were investigated using questionable root cause analysis tools. The result was ineffective corrective actions that may have reduced minor incidents but didn’t stop major accidents.

Companies improved their first-aid cases (or at least less were reported) but continued to have fatalities and major accidents at about the same rate.

(I worked at a site where supervisors learned to carry a first-aid kit to treat injuries and stop people from going to the site nurse/doctor. The result? First-aid cases dropped dramatically. Was this a safety improvement?)

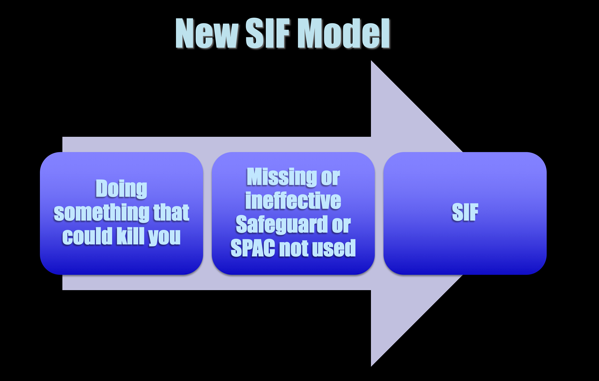

About a decade ago, some of the same people who revised the Heinrich Pyramid realized that correcting the causes of first-aid cases was not preventing fatalities. Thus began the research on significant injuries and fatalities (SIFs). The researchers came up with a new model:

This put the emphasis on industrial safety back on the activity (energy) that could kill you and the Safeguard that kept you safe.

This was a good start but insufficient. Why? Because some activities (process safety or driving) could always kill you.

In process safety, there are so many Safeguards that people begin to take the hazard (energy) for granted. Examples? Three Mile Island, Texas City Refinery explosion, Chernobyl, Deepwater Horizon.

In driving, there are very few safeguards to prevent the accident, but several incorporated into the design of the vehicle to try to prevent a fatality.

For process safety, you need to focus on maintaining the multiple, redundant Safeguards and investigate the failure of any Safeguard as an incident. Process safety requires an abnormal level of attention to detail.

In traffic safety, the focus on individual skills, adequate rest (fighting fatigue), and highway safety improvements seems to be the most logical approach.

Now to the title of this article.

Where are you?

- Are you still investigating incidents that aren’t worth investigating?

- Are you using ineffective root cause analysis tools to save time?

- Are you improving (or at least getting less reported) small incident but still having fatalities?

Perhaps it is time to learn about advanced root cause analysis and how it can be applied to small incidents that could cause major accidents (precursor incidents) and how this can be done in an efficient manner?

Call us at 865-539-2139 or e-mail us by CLICKING HERE to learn more about TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis and how it can help you stop major accidents.

Or, attend one of our TapRooT® Courses to learn to use the TapRooT® System. Here is a list of the dates and locations of upcoming 5-Day TapRooT® Advanced Root Cause Analysis Team Leader Training Courses:

In thinking and reviewing accidents in my career, we are missing the bottom of the pyramid and realistically the only piece that management can change. Exposures.

From this step up, we have to rely on our teammates to understand and follow the correct behavior for that specific circumstance. Yes, sometimes we can investigate and try to understand the why and make a change to our procedures, training or other behavior modifications, but again we must rely on our teammates.

However, if we (management) cause the exposures to increase or decrease, you can see a direct (although, it might take time to appear) reflection in the top of our pyramid.

Consider the British method for dealing with their Fall Potentials verses the American method. In most simple terms – the British system stops falls by eliminating the potential for falls. In the American system – we in put place to allow falls to happen, but have developed systems to catch people reducing their injuries. I wonder what would happen, if OSHA cited our companies every time that put their workers in harnesses as the first method of protection verses reviewing each and every fall potential and eliminating that fall potential exposure.

Safety is the present of safeguards and barriers, not the absence of incidents.

I agree that the pyramid has been misused. A number of years ago, I had a company auditor tell me that we were missing at least one serious incident based on the number of lower risk events.

It reminded me of a term from nuclear power school; gross conceptual error (GCE)!

I’m speculating of course, but perhaps your auditor was trying to indicate that your facility was overdue for a serious incident (statistically speaking that is). Much akin to how the pacific northwest is overdue for a major earthquake.

“Heinrich Pyramid” I have used for the past 25 years in my safety career. My mentor had me focus on the 600, because that represent “Near Misses”. they taught if I prevent the “Near Miss” the the Heinrich Ratio would not stand. So I always looking for the near miss or the opportunity for the near miss. I also look at the safety filters I have in place and if I need to replace the filter, a system or a process, to catch the near miss before it becomes a 300, 29, or 1.

“Constantly rediscover your safety systems and process so your filters won’t fail you”!

I have used the Heinrich Pyramid for 25 years as tool to educate management, supervisors, and employees of the theory of accident prevention and not as the silver bullet that will solve all of the safety issues at the firm. In supporting the Pyramid, I develop a safe system of operations around 8 elements: 1)Management engagement & accountability, 2) employee participation, 3) Safe operating practices, 4) H&S training, 5) Risk Management, 6) Incident Report, Investigation, & Root Cause Analysis, 7) Injury & Illness management, and lastly 8) Audits and Compliance. I have found that operational leaders that align with this model, 99% of the time, improved safety performance and lead to a reduction of incidents. The 1% that don’t align or pick and choose what elements they think are important, or don’t believe in the model at all. Tend to continue having incident and accidents including serious life changing events. All in all, I had consulted with one company that paid their senior leaders based on not having first aids and recordables! Guess what! we found under reporting, miss-classification of injuries and downright hiding of incidents in order for them to get their money while forgetting the pain and suffering of the employees. when presented with the data and facts we encountered, they chose to look the other way and we ended our relationship with the business. Sad but there are many firms that operate in that model. The simple message is called Duty of Care but that is for another of discussion.

While this is a good discussion, it does leave me wondering, Mark – are you saying we should accept less significant injuries and not put effort into preventing them? How do you determine what is “not worth investigating?” I don’t believe that is what you mean, but it would be good to get some clarity around that. I believe our goal should be zero injuries, but it is a balance weighing the cost and effort against the risk.

You have to decide what is worth the effort to investigate.

Everyone has resource limitations and certainly they should not get in the way of preventing fatalities. But what about paper cuts? How much effort should be put into preventing them?

Somewhere in between paper cuts and fatalities is the right effort that your company can afford to spend on improvement. The worst aren’t even preventing fatalities. The best tend to err toward fixing smaller stuff but don’t waste time on the trivial.