Heinrich Pyramid Misconceptions (Updated)

Do You Understand the Heinrich Pyramid?

Back in 2007, I wrote an article and gave several talks at professional society conferences about the accident pyramid called the “Heinrich Pyramid.” At the time, people were saying that the pyramid wasn’t accurate or useful for safety improvement.

Yesterday, I saw an article saying the Heinrich Pyramid had been “debunked.” I thought:

“They need to read this article.”

I think that much of the misunderstanding, misconceptions, debate, and debunked comments start with the misuse of what the pyramid represents.

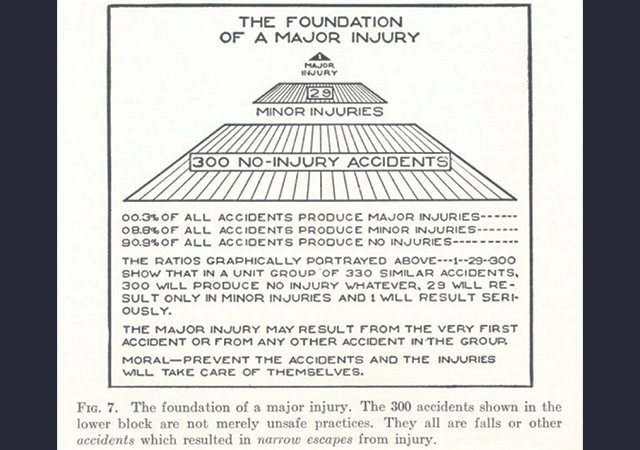

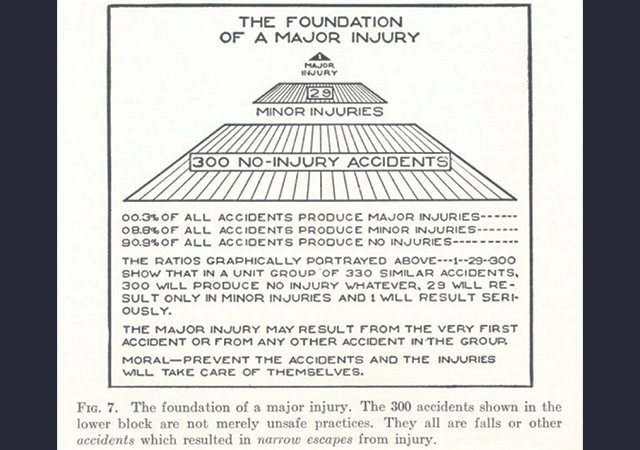

The original pyramid was based on Heinrich’s work in the insurance industry in the 1920s and 1930s. The writing below the pyramid (pictured above) states that, of 330 similar events, one will result in a major injury, 29 will result in a minor injury, and 300 will result in no injury.

Thus, because the events are similar, ALL 330 events could have caused a major injury, but 329 did not because of luck or other circumstances.

Others Introduce Modifications to the Model

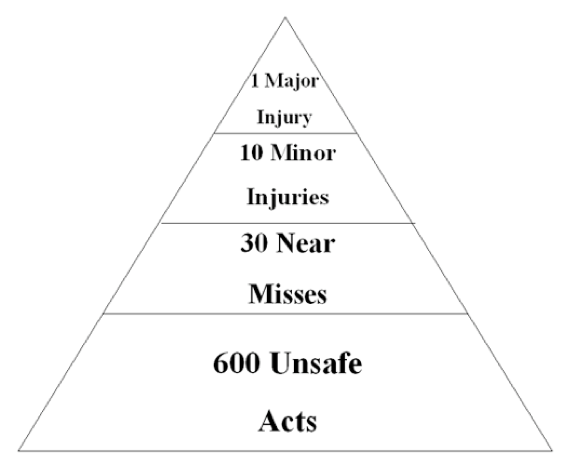

Over time, people modified Heinrich’s Pyramid. There was Frank Bird’s modification (Loss Control Management: Practical Loss Control Leadership, 1969)…

People interpreted this graph as meaning that for every major injury, there would be 600 unsafe acts. Sometimes, people didn’t say that the unsafe acts had to be capable of causing major injury. And that started some misconceptions.

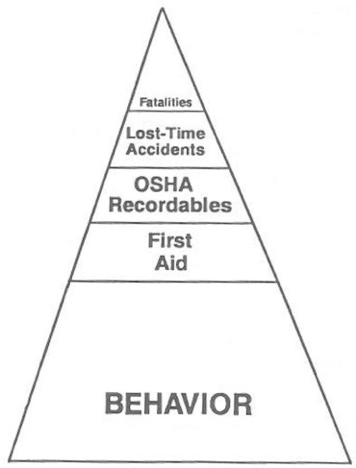

Also, there was the Krause, Hindley, and Hodson Pyramid (The Behavior-Based Safety Process, 1990)…

This replaced many of the terms on the pyramid and introduced behavior as the ultimate cause of injuries and fatalities. This caused more misconceptions.

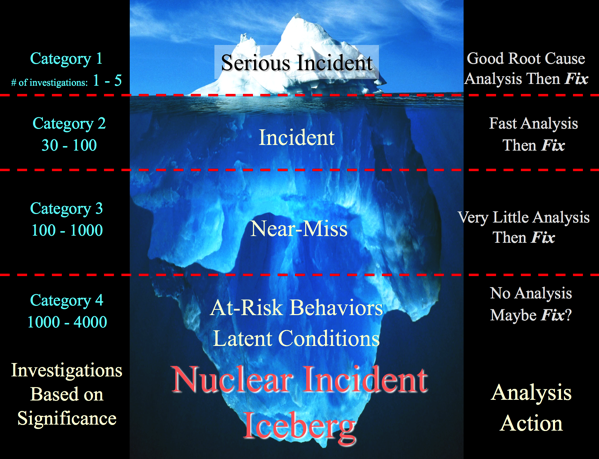

And finally, the nuclear incident iceberg…

Which, once again, focused on behaviors and latent conditions and didn’t mention the significance of the Safeguard that was being weakened or the energy involved.

Each of these modifications introduced misconceptions into performance improvement programs.

I think the basic concept of Heinrich’s Pyramid (that there are precursor events that, if identified, investigated, and fixed, could prevent major accidents) is just as true today as it was in 1920.

What Are the Misconceptions?

The new pyramids focused on unsafe acts and behaviors as the causes of major accidents. However, many lost the idea that the behaviors or unsafe acts had to be capable of causing a major accident/fatality or removing a Safeguard to a major accident or fatality. Thus, people began focusing on minor injuries to prevent major injuries or minor problems that could lead to reactor meltdowns or process safety-related fires and explosions.

That’s a misconception.

Heinrich didn’t say that ANY no-injury accident could cause a major injury. His pyramid was based on 1920s-1930s data from accidents that could cause a major injury. He didn’t say his data applied to all industries, nor that the ratio in his pyramid would remain constant for 100 years.

Thus, I would NOT say that the Heinrich Pyramid was debunked. I would say that it had been incorrectly modified and misused.

How Did Misconceptions Influence Safety Programs?

Stopping paper cuts won’t prevent major process safety-related accidents or industrial fatalities.

Nonetheless, some safety programs were misled into thinking that stopping first-aid cases would stop fatalities. Improvement programs were overwhelmed by small problems to investigate and fix. Investigators started using questionable root cause analysis tools to speed up investigations to reduce the impact of being overwhelmed.

Thus, even incidents with the potential to cause major accidents/process safety disasters/fatalities were investigated using questionable root cause analysis tools. The results? Ineffective corrective actions that didn’t solve the problems and stop major accidents.

Companies improved their first-aid cases (or at least fewer were reported) but continued to have fatalities and major accidents at about the same rate.

One example of the impact of the emphasis on minor injuries that I observed firsthand was that a supervisor at a site I was at learned to carry a first-aid kit to treat minor injuries and stop people from going to the site nurse/doctor. The result? First-aid cases dropped dramatically. This wasn’t a safety improvement. It was a way to improve statistics and keep management off the supervisor’s back.

The Next Step

More than a decade ago, some of the same people who revised the Heinrich Pyramid realized that correcting the causes of first-aid cases did not prevent fatalities. Thus began the research on significant injuries and fatalities (SIFs). The researchers developed a new model…

This energy model puts the emphasis back on the activity (which includes energy) that could kill you, and on the Safeguard that keeps you safe. However, the SIF people never really admitted that they had misused the Hienrich Pyramid.

Energy Theory & The Diamond

To improve on past Safeguard Analysis, the energy theory people proposed that only incidents involving hazards with a certain minimum energy should be investigated to prevent a fatality or a major injury. For example, if someone falls off a single step, this is unlikely to cause a significant injury because the energy is too low.

To keep this new theory grounded in science rather than guesswork, people separated real precursor accidents from minor incidents by calculating the energy required to cause a major injury for various types of energy. This helps consistently calculate what is “inside the diamond” (could cause a major injury) and what’s outside the diamond (doesn’t need to be investigated).

The Diamond…

Dr. Matthew Hallowell from the University of Colorado, Boulder (working with the Construction Safety Research Alliance) developed calculations for the energy types shown on the Energy Wheel below (from the Safety Function website)…

Here is a video about the energy wheel and calculating the energy that is required to cause a severe injury. When you click below, Matthew will discuss an app to calculate the energy required to cause a significant injury.

This work provides a method for determining whether an incident is a precursor (one that deserves investigation). That work provides an improved, calculated method for separating unimportant near-misses from significant near-misses. The key is …

“Could the energy present in the incident likely cause a serious injury or a fatality?”

Will this work result in a diamond-shaped pyramid? Perhaps. We shall see…

Industrial Safety vs. Process Safety

The Diamond and Energy Theory is a good start. But there is more to consider if your safety improvement efforts go beyond industrial worker safety. Some activities (think process safety, nuclear safety, or driving) can always kill you. (The energy is always there.)

In process safety, there are so many Safeguards that people begin to take the hazard (energy) for granted. Examples? Three Mile Island, Texas City Refinery explosion, Chornobyl, Deepwater Horizon. They start thinking that maintaining each redundant Safeguard isn’t that important. After all, there are always other Safeguards to prevent an accident. And one after another, the Safeguards fail until a major accident occurs.

After the accident, people proclaim that it is a freak accident, a fluke, a one-off accident that couldn’t have been anticipated. After all, they had calculated that it was almost impossible for that many Safeguards to fail.

For process safety, you need to focus on maintaining multiple redundant Safeguards and investigating the failure of any Safeguard as an incident. Process safety requires an abnormal level of attention to detail.

In driving, there are very few safeguards to prevent accidents, but several are built into the vehicle’s design to help prevent fatalities.

In traffic safety, the focus on individual skills, adequate rest (fighting fatigue), and highway safety improvements seems to be the most logical approach.

Where Are You?

Where are you when it comes to understanding the Heinrich Pyramid? How are you managing your investigations of precursor incidents? Or:

- Are you still investigating incidents that aren’t worth investigating?

- Are you using ineffective root cause analysis tools to save time?

- Are you reducing the number of small incidents (or at least fewer incidents reported) but still seeing fatalities?

There are ways to investigate precursor incidents efficiently AND effectively and get the most bang for your buck.

Better Root Cause Analysis

Perhaps it is time to learn about advanced root cause analysis and how to apply it to small incidents that could lead to major accidents (precursor incidents), and how to do so efficiently.

Call us at 865-539-2139 or e-mail us by CLICKING HERE to learn more about TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis and how it can help you stop major accidents.

Or, attend a TapRooT® Course to learn to use the TapRooT® System. Click on the link below for a list of the dates and locations of upcoming TapRooT® Training Courses:

https://store.taproot.com/courses

(The topic was originally discussed by Mark Paradies at several conferences in 2007 and 2008, and an article was written for the Root Cause Network˝ Newsletter at about the same time. We have greatly deepened our understanding of the pyramid and its application to safety improvement since those early discussions. This article was revised and republished from the original, published on June 3, 2020. If you have information that you would like to share about the pyramid or subsequent modifications and misconceptions to improve this article, please add your comments below.)

Very good article. I am one of those safety professionals who see the safety pyramid as incomplete and have tried to direct accident investigations towards the precursors and not the “stupid” act which caused the incident. Thanks for the info

You are welcome!

Dear Mark Paradies,

In my 1959, 4th edition, of Industrial Accident Prevention it is written: “[…], it is estimated that in a unit group of 330 accidents of the same kind and involving the same person, 300 result in no injuries, 29 in minor injuries, and 1 in a major lost-time injury.” Section 4. Foundation of a major injury pg.26

Also the author wrote that misunderstanding and misquotation of this ratio impels him to reiterate the fact that this ratio is an average.

People commonly rely on the pyramid but did not read the rationale on the book.

I agree completely.