Monday Accidents & Lessons Learned: The Worst U.S. Maritime Accident in Three Decades

The U.S.-flagged cargo ship, El Faro, and its crew of 33 men and women sank after sailing into Hurricane Joaquin. What went wrong and why did an experienced sea captain sail his crew and ship directly into the eye of a hurricane? The investigation lasted two years.

One of two ships owned by TOTE Maritime Inc., the El Faro constantly rotated between Jacksonville, Florida, and San Juan, Puerto Rico, transporting everything from frozen chickens to milk to Mercedes Benzes to the island. The combination roll-on/roll-off and lift-on/lift-off cargo freighter was crewed by U.S. Merchant Marines. Should the El Faro miss a trip, TOTE would lose money, store shelves would be bare, and the Puerto Rican economy would suffer.

The El Faro, a 790-foot, 1970s steamship, set sail at 8:15 p.m. on September 29, 2015, with full knowledge of the National Hurricane Center warning that Tropical Storm Joaquin would likely strengthen to a hurricane within 24 hours.

Albeit with modern navigation and weather technology, the aging ship, with two boilers in need of service, with no life vests or immersion suits, was equipped with open lifeboats that would not be launched once the captain gave the order to abandon ship in the midst of a savage hurricane.

As the Category 4 storm focused on the Bahamas, winds peaking at 140 miles an hour, people and vessels headed for safety. All but one ship. On October 1, 2015, the SS El Faro steamed into the furious storm. Black skies. Thirty to forty foot waves. The Bermuda Triangle. Near San Salvador, the sea freighter found itself in the strongest October storm to hit these waters since 1866. Around 7:30 a.m. on October 1, the ship was taking on water and listing 15 degrees. Although, the last report from the captain indicated that the crew had managed to contain the flooding. Soon after, the freighter ceased all communications. All aboard perished in the worst U.S. maritime disaster in three decades. Investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) were left to wonder why.

When the NTSB launched one of the most thorough investigations in its long history, they spoke with dozens of experts, colleagues, friends, and family of the crew. The U.S. Coast Guard, with help from the Air Force, the Air National Guard, and the Navy, searched in a 70,000 square-mile area off Crooked Island in the Bahamas, spotting debris, a damaged lifeboat, containers, and traces of oil. On October 31, 2015, the USNS Apache searched and found the El Faro, using the CURV 21, a remotely operated deep ocean vehicle.

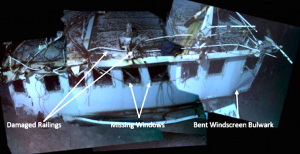

Thirty days after the El Faro sank, the ship was found 15,000 feet below sea level. The images of the sunken ship showed a breach in the hull and its main navigation tower missing.

Finally came the crucial discovery when a submersible robot retrieved the ship’s voyage data recorder (VDR), found on Tuesday, April 26, 2016, at 4,600 meters bottom. This black box held everything uttered on the ship’s bridge, up to its final moments.

The big challenge was locating the VDR, only about a foot by eight inches. No commercial recorder had ever been recovered this deep where the pressure is nearly 7,000 pounds per square inch.

The 26-hour recording converted into the longest script—510 pages— ever produced by the NTSB. The recorder revealed that at the outset, there was absolute certainty among the crew and captain that going was the right thing to do. As the situation evolved and conditions deteriorated, the transcript reveals, the captain dismissed a crew member’s suggestion that they return to shore in the face of the storm. “No, no, no. We’re not gonna turn around,” he said. Captain Michael Davidson then said, “What I would like to do is get away from this. Let this do what it does. It certainly warrants a plan of action.” Davidson went below just after 7:57 p.m. and was not heard again nor present on the bridge until 4:10 a.m. The El Faro and its crew had but three more hours after Davidson reappeared on the bridge, as the recording ends at 7:39 a.m., ten minutes after Captain Davidson ordered the crew to abandon ship.

This NTSB graphic shows El Faro’s track line in green as the ship sailed from Jacksonville to Puerto Rico on October 1, 2015. Color-enhanced satellite imagery from close to the time the ship sank illustrates Hurricane Joaquin in red, with the storm’s eye immediately to the south of the accident site.

The NTSB determined that the probable cause of the sinking of El Faro and the subsequent loss of life was the captain’s insufficient action to avoid Hurricane Joaquin, his failure to use the most current weather information, and his late decision to muster the crew. Contributing to the sinking was ineffective bridge resource management on board El Faro, which included the captain’s failure to adequately consider officers’ suggestions. Also contributing to the sinking was the inadequacy of both TOTE’s oversight and its safety management system.

The NTSB’s investigation into the El Faro sinking identified the following safety issues:

- Captain’s actions

- Use of noncurrent weather information

- Late decision to muster the crew

- Ineffective bridge resource management

- Company’s safety management system

- Inadequate company oversight

- Need for damage control plan

- Flooding in cargo holds

- Loss of propulsion

- Downflooding through ventilation closures

- Need for damage control plan

- Lack of appropriate survival craft

The report also addressed other issues, such as the automatic identification system and the U.S. Coast Guard’s Alternate Compliance Program. On October 1, 2017, the U. S. Coast Guard released findings from its investigation, conducted with the full cooperation of the NTSB. The 199-page report identified causal factors of the loss of 33 crew members and the El Faro, and proposed 31 safety recommendations and four administrative recommendations for future actions to the Commandant of the Coast Guard.

Captain Jason Neubauer, Chairman, El Faro Marine Board of Investigation, U.S. Coast Guard, made the statement, “The most important thing to remember is that 33 people lost their lives in this tragedy. If adopted, we believe the safety recommendations in our report will improve safety of life at sea.”